1.

Introduction

Operation Pocket-93 was among the many violent military campaigns during the wars fought between 1991 and 1995 on the territory that once formed the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY).

The war in Croatia was linked to its move towards independence from Yugoslavia, a process initially pursued peacefully, but later escalating into armed conflict. At the same time, tensions between Croats and Serbs in Croatia grew, gradually turning into violence, and from the summer of 1991, the situation can accurately be described as war. As the Croatian state emerged, a part of the Croatian Serbs who did not accept it seceded, with backing from the Milošević regime in the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY).

On October 5, 1993 (author’s comment), I personally went to see the Medak Pocket. Nothing I had read prepared me for what I saw there. Nearly everything had been destroyed, levelled to the ground, clearly intentionally. I have never seen anything like it, not even now, despite having served in conflict zones like Mostar, Sarajevo, Beirut, Mogadishu, Baghdad, and the ruined towns of Angola, among others.

— Cedric Thornberry, UN Civilian Representative for Yugoslavia, Deputy Commander of UNPROFOR

2. Area of the Operation Pocket-93

During the conflict in the Croatian territory, the town of Gospić was under the control of the Croatian Army (HV). In 1991, the JNA and rebel Serbs seized part of the municipality, and the wider area was exposed to warfare damage. War crimes — against both Croatian and Serb civilians and soldiers — were committed both in combat and through atrocities against those captured.

Gospić lay near the military demarcation line between the armed forced of the Republic of Croatia and the RSK, and it also headquartered units of the Croatian Army. By mid-1993, it was frequently targeted by artillery attacks from the RSK's Army of the Serbian Krajina (ARSK). From July 1993, Croatian Army reconnaissance raids and diversionary actions became more frequent, intensifying in August. This escalation prompted the Croatian Army leadership to plan a military operation to seize the approximately 50 square kilometres of territory known as the Medak Pocket, which included the villages of Lički Čitluk, Počitelj, Divoselo, and Medak, areas where the vast majority of inhabitants had declared themselves Serbs in the 1991 census.

Population

Population of the Municipality of Gospić according to the 1991 census

the Municipality of Gospić

29.049

Divoselo

Čitluk

Počitelj

UNPA and Pink Zones in Croatia

In 1993, the Medak Pocket fell within what were known as "pink zones", areas located between territories controlled by the Republic of Croatia (RH) and areas under UN protection, the so-called UNPA zones. Both the UNPA and adjacent pink zones were regions where Serbs constituted a majority or significant minority, and where inter-community tensions had escalated into armed conflict. Indeed, these territories were part of the then Republic of Serbian Krajina.

UNPA Sector North

UNPA Sector North

UNPA Sector East

UNPA Sector East

UNPA Sector West

UNPA Sector West

UNPA Sector South

UNPA Sector South

Pink Zones

Pink Zones

Occupied Territory Borders

Occupied Territory Borders

UNPA Sector Borders

UNPA Sector Borders

3. Planning and Objectives of Operation Pocket-93

The Chief of the General Staff of the Croatian Army (GSHV), Janko Bobetko, ordered preparation of the initial plans for a broader operation to liberate the Medak Pocket in mid-1993. From then until September, numerous members of the Croatian Army and the Special Police of the Ministry of the Interior (MUP) were involved in operational planning.

The designated routes of advance and responsibilities for the Special Police were as follows: Veliki Sokolovac — Bukova Glava — Debela Glava — Čitluk.

For the Croatian Army, the main axis was Bilaj — Čitluk, with the final objective being along the following route: Drljići — Memedovo Brdo — Kriva Lika — Ribnik.

In the Medak Pocket, the Croatian Army believed that elements of the ARKS's 9th Mechanised Brigade from Gračac and the 103rd Brigade from Donji Lapac were located there and assessed to be unprepared for Croatian forces' attack.

Operation Pocket-93 had two principal objectives:

1.Military objectives

Military objectives were to secure a tactically significant area of the Medak Pocket, relieve the south-eastern flank of Gospić and prevent RSK forces from cutting the Gospić — Karlobag route. This also included eliminating artillery threats to Gospić emanating from the villages in the Medak Pocket area, which would demonstrate the strength to the enemy and boost civilian morale. Alongside all of this, another objective was to capture the valley north of the Maslenica Bridge in order to additionally secure access to that area;

2.Ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing was executed through war crimes. The entire zone was subjected to the systematic and ruthless destruction of property and infrastructure, a feat carried out by the Croatian Army and Special Police, alongside semi-controlled killings, and looting. Achieving these goals was motivated by personal gain through looting and revenge driven by hatred.

4. Command Structure and Responsibility

A special combat group called Sector 1 was formed to carry out the operation. It was commanded by Mirko Norac. Outside Sector 1, the Special Police of the Ministry of the Interior (MUP) participated, under the command of Mladen Markač, with field coordination by Željko Sačić.

Janko Bobetko commanded the operation overall from the Croatian Army General Staff (GSHV) in Zagreb, appointing GSHV officer Davor Domazet as his field delegate with command authority. Domazet was in continuous communication with Bobetko.

Two parallel chains of command existed in this operation:

- A formal chain, with written orders, largely coordinated by the Gospić Military District (MD) under Rahim Ademi;

- And an informal chain, consisting of direct oral orders from Bobetko at the Croatian Army General Staff, and which included Domazet, Norac, Markač, and Sačić.

While the formal line was ostensibly in place, the informal chain was the primary driver of the operation's execution.

The operation involved approximately...

... and

Brigades

Croatian Armed Forces

9th Guards Brigade

9th Guards Brigade

111th Infantry Brigade of the Croatian Army

111th Infantry Brigade of the Croatian Army

Croatian Army Home Guard

Croatian Army Home Guard

Lovinac Home Guard

Lovinac Home Guard

Special Police Units

Special Police Units

Army of the Republic of Serbian Krajina

9th Mothorised Brigade of the Serb Krajina Army from Gračac

103rd Brigade from Donji Lapac

9th Mothorised Brigade of the Serb Krajina Army from Gračac

103rd Brigade from Donji Lapac

5. Chronology of the Operation

917 September 1993

6. Ethnic Cleansing

6.1—Killings and Torture of Civilians and Prisoners of War

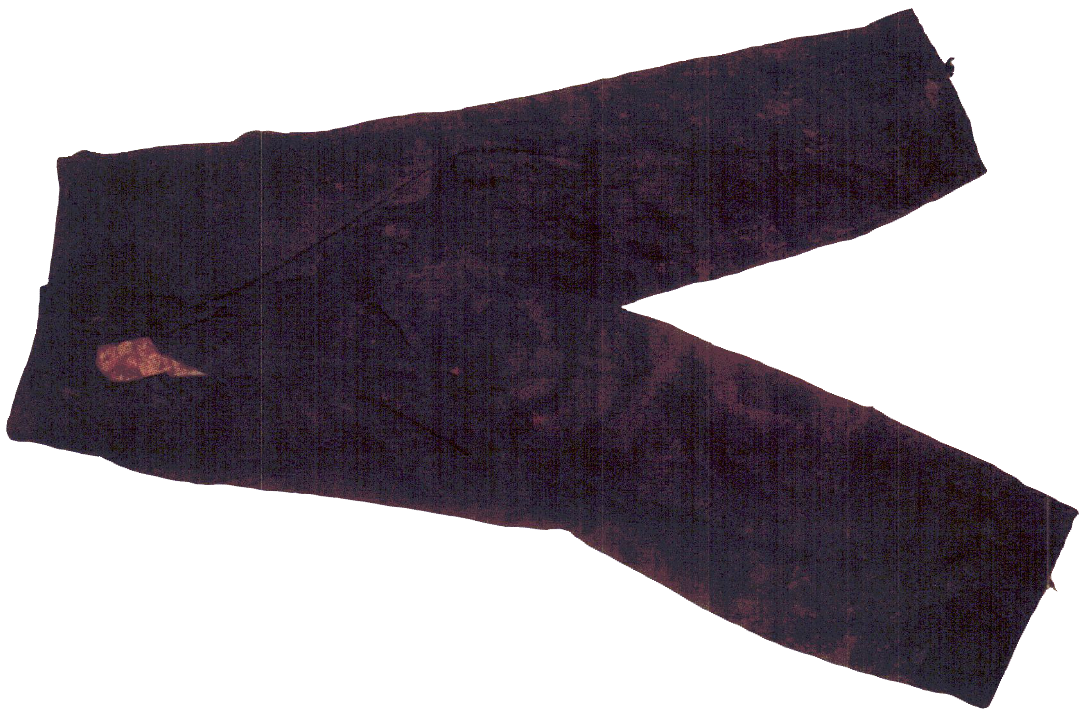

Croatian soldiers and Special Police killed civilians and prisoners of war during the operation in the villages of Počitelj, Divoselo, and Lički Čitluk, which they had captured. It is evident that the crimes were committed both in the zone of responsibility of HV Sector 1 and in the zone of responsibility of the Special Police of the Ministry of the Interior of the Republic of Croatia, and that people were killed and tortured from the very first day of the operation — 9 September 1993 — until its end. At the trial of Ademi and Norac before the County Court in Zagreb, survivors from the villages testified about the violence. Some had witnessed killings and torture themselves. A few members of Croatian forces also spoke out, while UNPROFOR soldiers and policemen only saw the consequences of the killings and destruction.

Croatian soldiers and Special Police killed civilians and prisoners of war during the operation in the villages of Počitelj, Divoselo, and Lički Čitluk, which they had captured. It is evident that the crimes were committed both in the zone of responsibility of HV Sector 1 and in the zone of responsibility of the Special Police of the Ministry of the Interior of the Republic of Croatia, and that people were killed and tortured from the very first day of the operation — 9 September 1993 — until its end. At the trial of Ademi and Norac before the County Court in Zagreb, survivors from the villages testified about the violence. Some had witnessed killings and torture themselves. A few members of Croatian forces also spoke out, while UNPROFOR soldiers and policemen only saw the consequences of the killings and destruction.

6.2—Destruction of Property and Looting

The complete destruction of private and commercial property in the villages and hamlets of the Medak Pocket is best documented in the reports written on the basis of direct field observation by members of the Canadian battalion of UNPROFOR and the UN Civilian Police, as well as in the testimonies of villagers and members of the engineering unit of the 9th Guards Mechanised Brigade (9th GMB).

The complete destruction of private and commercial property in the villages and hamlets of the Medak Pocket is best documented in the reports written on the basis of direct field observation by members of the Canadian battalion of UNPROFOR and the UN Civilian Police, as well as in the testimonies of villagers and members of the engineering unit of the 9th Guards Mechanised Brigade (9th GMB).

6.3—Concealment of Crimes

The scale of the violence, especially the number of killings in the area of Operation Pocket-93, was concealed through the hiding of corpses.

Protected Witness No. 9, who testified at the trial of Mirko Norac and Rahim Ademi and who was a member of the engineering unit of the 9th Guards Mechanised Brigade, stated that his commander — Chief Engineer of the 9th Guards Mechanised Brigade, Goran Blažević — ordered him to dispose of the corpses. He then went with two military policemen and a colleague from the unit to collect mines, explosives, slow-burning fuses, and detonators, which he brought to a large house on the outskirts of Gospić. The house had an incomplete septic pit, and the surrounding buildings were already demolished. A refrigerated lorry also arrived at the site with a driver and, according to his testimony, three drunken soldiers from Home Guard units.

The scale of the violence, especially the number of killings in the area of Operation Pocket-93, was concealed through the hiding of corpses.

Protected Witness No. 9, who testified at the trial of Mirko Norac and Rahim Ademi and who was a member of the engineering unit of the 9th Guards Mechanised Brigade, stated that his commander — Chief Engineer of the 9th Guards Mechanised Brigade, Goran Blažević — ordered him to dispose of the corpses. He then went with two military policemen and a colleague from the unit to collect mines, explosives, slow-burning fuses, and detonators, which he brought to a large house on the outskirts of Gospić. The house had an incomplete septic pit, and the surrounding buildings were already demolished. A refrigerated lorry also arrived at the site with a driver and, according to his testimony, three drunken soldiers from Home Guard units.

7. Judicial Proceedings and Accountability for Crimes

May 2001

September 2002

May 2004

September 2005

September 2005

May 2008

May 2015

October 2016

8. Victims

CIVILIANS • 29

- Bjegović, Bosiljka (Stevo/Stevan),27 Dec 1909

- Bjegović, Milka (Đuro),22 May 1947

- Jelača, Ljiljana (Mićan),3 Jul 1956

- Jerković, Nikola (Ilija),1 Jan 1961

- Jović, Anđelija (Dobroslava),6 May 1933

- Jović, Dmitar (Mile),19 Apr 1937 / 19 Mar 1937

- Jović, Marinka (Branko),4 Aug 1939

- Krajnović, Đuro (Toma),1 May 1911

- Krajnović, Neđeljka (Samojlo),2 Sep 1921

- Krajnović, Pera (Đuro),1 Jan 1907

- Krajnović, Stana (Jovo),1 Jan 1926

- Krajnović, Štefica (Josip),8 Feb 1931 / 2 Feb 1931

- Kričković, Sara (Trivun),30 Oct 1921

- Kričković-Živić, Ljubica (Trivun),30 Sep 1929

- Matić, Milan (Mile),1 Jan 1949

- Pejnović, Mile (Luka),1 Jan 1935

- Pjevač, Boja (Dane),14 Jan 1925

- Potkonjak, Janko (Stevan),1 Jan 1931

- Potkonjak, Marko (Milan),11 May 1934

- Rajčević, Milan (Nikola),24 Apr 1962

- Rajčević, Sava (Milan),1 Jan 1930 / 1 Jan 1931

- Vujnović, Ankica/Ana (Tomo),19 Mar 1934

- Vujnović, Branko (Stevo/Stevan),8 Feb 1948

- Vujnović, Đuro (Nikola),20 Jul 1927

- Vujinović/Vujnović, Stevan/Stevo (Dmitar),15 Oct 1922

- Vujnović, Momčilo (Dimitar/Dmitar),27 Nov 1936 / 19 Nov 1936

- Vujnović, Nikola (Jovan),13 Mar 1946 / 1 Jan 1947

- Vujnović, Boja (Đuro),1 Jan 1909

- Vujnović, Nikola (Đuro),21 Jun 1954

SOLDIERS • 7

- Basara, Željko (Milan),23 Aug 1971

- Ciganović, Miodrag (Mile),1 Oct 1957

- Ćopić, Željko (Milan),28 Mar 1958

- Despić, Stanko (Risto),23 Sep 1952

- Krivokuća, Dane,1963 or 1964

- Pavlica, Dragan,1968

- Stojisavljević, Nikola (Spasenije),1952

The data on those killed during Operation Pocket-93 have not been precisely documented.

Publicly available sources provide differing figures. Thus, the ICTY indictment against Rahim Ademi states that "during the Croatian military operation in the Medak Pocket, at least 38 Serb civilians from the area were unlawfully killed, and others suffered serious injuries. Many of the killed and wounded civilians were women and elderly persons. In addition, Croatian forces killed at least two Serb soldiers who had been captured and/or wounded. Details on some of the victims, namely 21 civilians and two soldiers, are contained in the annex to the indictment."

9. Contemporary Challenges

The area of today's Medak Pocket still consists of abandoned and devastated villages. According to the 2021 census, two people live in Počitelj, five in Lički Čitluk, and only one person in Divoselo.

Population of the Municipality of Gospić according to the 1991 census

the Municipality of Gospić

29.049

Population of the Town of Gospić according to the 2021 census

the Town of Gospić

11.502

Divoselo

Čitluk

Počitelj

In Divoselo, no mine clearance was carried out after the war, and of 118 applications for house reconstruction, only 11 were approved. The village has no electricity, its wells are polluted, and therefore no permanent inhabitants remain. The situation in Počitelj and Čitluk is similar, if not identical.

In the thirty-two years since Operation Pocket-93, no additional investigations or trials have been conducted to identify other responsible commanders and direct perpetrators of the crimes.